By Some London Foxes.

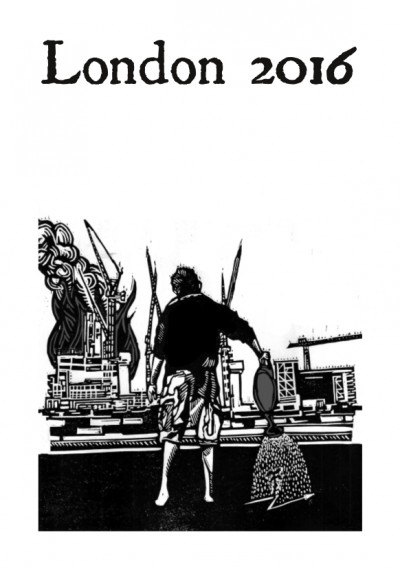

This is a small contribution towards mapping the terrain of social conflict in London today.

First, it identifies some big themes in how London is being reshaped, looking at: London’s key role as a “global hub” for international finance capital; how this feeds into patterns of power and development in the city; and the effect on the ground in terms of two kinds of “social cleansing” – cleaning out undesirable people, and sanitising the social environment that remains.

Second, it surveys recent resistance and rebellion to this pattern of control including the short-lived “grassroots housing movement” of last winter, the confrontational Aylesbury Estate occupation, anti-raids mini-riots, and some riotous street parties.

Third, it tries to stimulate some positive thinking about what we can do now to help anarchy live in “the belly of the beast”.

It doesn’t cover everything important and doesn’t offer “the answers”. But maybe it can help kick off some discussion and some action.

Note from Squat!net: Below we include two chapters ‘Some Seeds’ and ‘Aylesbury occupation’ (2.2. and 2.3) that focus on the early residential-based protest occupation movement, providing summarises and analysis of recent squatting resistance in London. However, naturally the text in it’s entirety is further recommended to fully comprehend the capital’s unique economic structure, within a context of a broader struggle against the state and capital, in order to ignite further uprisings against the enemy.

You can read the full text on Rabble or download the booklet as a 16-page PDF: in reading order or ordered for booklet printing.

2. Resistance and Rebellion

2.2 Some seeds

Three and a half years later, in the winter of 2014-15, we began to see some small murmurings of self-organised resistance at the frontlines of spreading development.

In September 2014, a group of single mothers threatened with eviction from a hostel, who went by the name “Focus E15”, occupied a small block of flats in the Carpenters’ Estate in Stratford, East London. This was a housing estate right next to the site of the 2012 London Olympics, that had been mostly “decanted” and left open for another classic demolition and gentrification scheme. The occupation only lasted a few weeks but attracted much attention and inspired others.

Similar occupations and high-profile protests sprouted in the next months across other working class neighbourhoods: New Era Estate in Hoxton (East End); Cressingham Gardens and the Guinness Estate in Brixton; West Hendon and Sweet’s Way estates in North London. The same period also saw a rise of “radical casework” housing activism championed by groups such as Hackney Renters (aka DIGS) and Housing Action Southwark and Lambeth (HASL): fighting individual evictions with tactics from legal action to pickets, office occupations, or direct resistance.

The left and liberal media salivated over these campaigns. All the elements were there. The firgureheads were mothers, or at least “local working class women”, who could be hailed as “genuine” political subjects rather than “outside agitators”. They were ranged aginst cartoon villain politicians like the deeply unpleasant and corrupt mayor of Newham, Sir Robin Wales. They practised “civil disobedience” or “non-violent direct action”, which looked good for the cameras but didn’t overstep the bounds of civility. Celebrities rallied round for sleepovers and photo ops, comedy-messiah Russell Brand leading the way.

The local occupations were relatively autonomous, in that the traditional recuperating forces of the Left – the Labour Party, the unions, the trotskyist Socialist Workers Party – were mostly absent. The SWP had been smashed by a big rape scandal, while Labour appeared in terminal decline. The ground was perhaps fertile for new forms of self-organisation and unmediated rebellion.

Although, behind the scenes, there were some moves towards more centralised political organisation. A number of the E15 and other activists were involved with the small marxist “Revolutionary Communist Group”. The big trade union Unite, the main funder of the Labour Party, handed out some money and professional organisers, and sponsored a London-wide forum called the “Radical Housing Network”.

The Radical Housing Network called for a major demo – the “March for Homes” – on 1 February 2015. During this demo, a group of anarchist squatters intervened with a breakaway “Squatters Bloc”, which upped the ante with an ambitious and combative occupation on the Aylesbury Estate.

Aylesbury occupation

The idea of mass squatting one of Southwark’s big “decanted” demolition estates had become a holy grail of South London squatting legend. In 2010-11, an exciting time of student mini-riots and occupations that perhaps helped feed the August 2011 uprising, London anarchos held a number of planning meetings for a proposed occupation of the Heygate. These came to nothing: taking over a big estate and holding it against the police seemed beyond our capacities, we talked for months and did nothing. The Aylesbury scheme, on the other hand, was totally last minute. It seemed like a mad experiment, and it didn’t last long. But for the two months it did, it was about the most exciting thing to happen in the city for a good while, and may hold useful lessons for the future.xv

On the day, a breakway bloc of about 150 diverted from the March for Homes down south to take the estate. Very few of those stayed that night, but over the next days numbers grew and the occupation took hold. On the first full day, squatters made contact with estate residents who had campaigned for years against the demolition, held an open air meeting, and relationships began to form. Following the example of E15, the idea was to have one house as a collective space open every day for people to gather, exchange, plot, talk. Visitors arrived from Stratford, Hackney, and all over South London. But it would also need more permanent residents to defend the space and bring it to life.

From the start, there were some obvious lines of tension: between anarcho-squatters, leftist tenant campaigners, other locals of various backgrounds and allegiances, students arriving to take pictures or write dissertations, not to mention a drug-fuelled money-hungry rave crew appearing on the scene. Some of these encounters were provocative and productive, some a headache.

For the first two weeks, the authorities had no plan, and left the occupation alone to flourish and grow. Then they came with the first eviction attempt on 17 February, bringing up to 100 riot cops. The occupation outfoxed them: we had prepared a second building, defended by barricades the council itself had built in a vain attempt to keep us out, and got enough people down to out-number the riot police. Although the immediate area around the occupation was empty awaiting demolition, the blocks nearby were hostile territory for the state, and the local police were well scared of starting a serious riot here. We won the night; they de-escalated.

Which was the sensible move for them. In the next weeks, the police avoided major confrontation, while the local council wore down the occupation by siege. They built a £150,000 razor-wire topped fence around the occupied area, locking us off from the rest of the estate, and hired a force of private security guards (easily costing hundreds of thousands more) to contain and harass. It worked. Only the most “hardcore” occupiers, without many other commitments, could stay long under these conditions, and numbers gradually decreased as other squatters found easier accommodation and supporters got locked out. The occupation went out with one last bang, pulling down several fences in a well planned and well executed final demo on 2 April (which, again, Southwark Police sensibly let happen.)

In the final analysis, London’s existing squatting networks didn’t have the strength, the numbers, to hold the occupation for long. And although the occupiers saturated the whole estate and surrounding area with posters, leaflets, messages in paint or chalk, knocked on doors, held street stalls, called meetings, demos, gatherings, etc., the vast majority of Aylesbury residents weren’t roused to action. Many opposed the development and supported the occupation, but with a few very notable exceptions this support was passive. The occupation did not manage to help activate this passive opposition.

Southwark Council’s decanting strategy, so far, has proved effective. The estate has been left to deteriorate for 20 years, so that tenants start to believe anything else might be better. Those who agree to move are offered shiny new homes. Any who refuse face losing their tenancy and any chance of an affordable home in central London. And the whole scheme is phased over years, people being moved out in dribs and drabs rather than in one dramatic mass eviction.

Perhaps the biggest threat the occupation posed, as the police (if not the council) certainly realised, was that rebellion in the emptied part of the estate would spread to the youth and other confrontational elements in the blocks and streets nearby. The siege succeeded in containing us and preventing this.