As a squatter in Amsterdam, looking back on the past year is painful. 2019 dealt heavy blows to a movement that didn’t seem capable of much more than taking the beating. The city has lost its largest squats and despite numerous squatting actions, hardly any new buildings have survived the end of the year. What’s more, politicians tried to introduce a law at national level to further criminalise squatters while the media reported time and time again how afflicted property owners are being deceived repeatedly by squatters. To top it all off, the mayor concludes the year with a report on a new policy designed to implement a more rigorous approach to squatting.

As a squatter in Amsterdam, looking back on the past year is painful. 2019 dealt heavy blows to a movement that didn’t seem capable of much more than taking the beating. The city has lost its largest squats and despite numerous squatting actions, hardly any new buildings have survived the end of the year. What’s more, politicians tried to introduce a law at national level to further criminalise squatters while the media reported time and time again how afflicted property owners are being deceived repeatedly by squatters. To top it all off, the mayor concludes the year with a report on a new policy designed to implement a more rigorous approach to squatting.

There’s not much left to say beyond 2019 having been a rather grim year, making it difficult to paint a hopeful picture for squatting in Amsterdam in 2020.

We look back on a year in which we, above all, lost a lot.

ADM

Starting off with the ADM eviction. To be expected but nonetheless painful. 21 years of living, being alive, working, and partying under the banner of freedom, all the while aspiring to be an example for the rest of the city and the world. A place, where everyone felt welcome (apart from a few exceptions in uniform), money wasn’t given any power (besides this one somewhat expensive annual festival), creativity had free reign and where people together have built a beautiful miniature world in an otherwise fairly ugly part of the city. After years of court cases, political posturing and negotiations with the municipality and other relevant parties, the curtain fell for good on January 7. In doing so, the UN ruling that an eviction would be in breach of international human rights treaties, was brushed aside. Confronted by an army of police, supported by aggressive enforcement and violent security (engaged by Chidda), there was little symbolic resistance during the eviction, whereupon ADM-residents had to retreat to a place called Slibvelden (which lives up to its name).

ADM fell into the hands of Chidda BV, the heir of B. Lüske (former owner of the ADM), whose connections with the criminal underworld were widely known, also thanks to his liquidation in 2003. Key figure in the deal between the city and Lüske was Ton Hooijmaijers, then lid of the VVD, meanwhile convicted of corruption. Also, Mister P. Koole, owner of Koole BV and future tenant of the terrain, was arrested in Italy this summer, because he was wanted by Interpol. Wonderful crowd – These are the parties the municipality wants to do business with?

Bajesdorp

Also Bajesdorp had to suffer this year. Similar to ADM, it used to be a place of dwelling and living as well as singing and organising and was an invaluable space for the scene, the city and far beyond. This place, just like ADM, had to make way for big money. After years of intensive negotiations with the municipality and the owners on legalisation, the plans for Bajesdorp 20, a breeding space to be build next to former Bajesdorp, are finally in place.

October 2019 – Demolition in progress at Bajesdorp

October 2019 – Demolition in progress at Bajesdorp

ME

The Mobiele Eenheid, a collective that squatted a building on Gedempt Hamerkanaal in the north of Amsterdam in October 2018 in order to provide a space, of which there once were so many, i.e. a social centre, where people live. A space that was to show the added value of the squatting scene to the rest of the city and bring people together in a shared social struggle, but where eventually, before the eviction at the beginning of this year, not much more than a few fun parties were organised.

Construction works started quite late in the year and only in parts of the building, the large warehouse, where people used to hang out at the bar the year before, looks as if it still smells like stale beer. The luxury hotel promised by owner Uri Ben Yakir is yet to come. Same goes for the new location Mobiele Eenheid was going to open. Despite the intention to continue the activities and/or struggle after the eviction, nothing happened in the remainder of 2019 and it seems as if “the first base of Mobiele Eenheid” will also be the last.

Mayor Halsema demonstrates clearly what she really meant by “protecting the fringes that make this city so beautiful”. Shady underworld figures are given free reign as long as they provide enough money, while our underground is torn apart and its remnants have to be swept under the carpet as quickly as possible.

Lutkemeerpolder

The story of the Lutkemeerpolder is potentially even more symptomatic of how the city council intends to shape this city. Even though it isn’t a squat, it’s still a good example, especially for all of those who still believed that a ‘green-left’ government could have resulted in a different city.

This natural area is the last part of the city where the land is still suitable for agriculture. Yet, the government is of the opinion that it has to be covered in industry. As a result, it might have been the care-farm’s De Boterbloem final year, after a century of existence. The only space in Amsterdam where sustainable organic/ecological food was grown and locally distributed on this scale could have been an example for how climate change might have never advanced this far. Instead, it has to make way for a distribution centre to which the most nonsensical products will be shipped from all over the world for temporary storage…

Again, Ton Hooijmaijers has to be mentioned as a concerned party, who succeeded to enrich himself and others by realising the deal between municipality and investors. Once again, the municipality shows that proven corruption doesn’t have to be a deterrent, if money is to be made and in its pursuit of profit, green is entirely left aside, regardless of who you voted for.

September 2019 – Lutkemeerpolder eviction

September 2019 – Lutkemeerpolder eviction

Many losses, little in return

Not only squatted social centres had to suffer. Throughout the entire city great losses have been made, while very few squats remain. In quick succession Strekkerweg, Meeuwenlaan and Sophialaan were evicted; three big buildings where an awful lot of fun things happened, and which offered many a squatter refuge in the few years of their existence (but for which people still couldn’t come up with better names). Unfortunately, many more squatted houses had to close their doors this year, whereas the number of still existing spaces squatted in 2019 can be counted on one hand and even then, you don’t need all your fingers. As with many of the evicted buildings, little to nothing happened since the squatters’ departure. Occasionally some demolition works, every now and then a sign saying ‘I am working here’, but far too often an anti-squat poster appears in the window, giving you an invisible but very tangible middle finger every time you walk past your old house.

Time and again, municipality officials and/or judges go along with the shady, false arguments provided by property owners, who successfully claim urgency for evictions with false promises and vague plans. Yet, they are rarely if ever held accountable for their responsibilities and false promises. Emptiness and decay are preferable in the eyes of the municipality, seemingly more so than use through inhabitation by residents who are willing to roll up their sleeves and make this increasingly ugly city a little more beautiful.

August 2019, van ‘t Hofflaan 16 squatted in Frankendael

August 2019, van ‘t Hofflaan 16 squatted in Frankendael

Kadoelen

Sometimes this goes so far that property owners aren’t hindered to take matters into their own hands to evict their property. The former café on Landsmeerdijk in Amsterdam Noord was squatted in January this year. Soon after, the owner, under the watchful eyes of the police, evicted the place by ramming a dormer window of the roof with a digger while the squatters barely managed to get out of the building in time.

The café had been standing empty for quite some time, since the former operator was summoned to close his café after years of decay caused by poor maintenance. Eventually, the building was bought by notorious speculator F.F. Prud’homme de Lodder, who was planning to build luxury apartments in its place but didn’t get the necessary permits due to the building’s monumental status, meaning it can’t be demolished legally. To the relief of many people in the neighbourhood, who supported the squatters fully and would have liked to see them revive this historical place, which had been a café for four centuries.

To no avail. The municipality had decided to evict on grounds of unsafe living conditions whereupon the owner put words into action and half demolished the building with a digger, while the police was watching silently but seemingly in agreement. The rejection of his requested demolition permits didn’t seem to pose any problem. Instead of granting the squatters the time to save this historical building from further decay, the dilapidated café is left to rot entirely. It is presently secured by fences that warn of danger of collapse and where last year had been a dormer window is now a torn blue tarp in its place.

February 2020 – Former Café Kadoelen, Landsmeerderdijk in Amsterdam Noord

February 2020 – Former Café Kadoelen, Landsmeerderdijk in Amsterdam Noord

Amstel

The story of Amstel 45, a (once beautiful) canal house on the Blauwbrug, near Waterlooplein, is similar. It was squatted in September after years of emptiness and decay. The owner, Mr. J.C.M. Veldhuijzen, is with 512 properties to his name one of the most notorious speculators in Amsterdam. Veldhuijzen has been in conflict with the municipality for years due to his plans for the building. He doesn’t receive the required permits and instead was imposed a construction stop, following illegal works that have caused considerable damage to the building. The court proceedings between Veldhuijzen and the municipality were ongoing during the time it was squatted. Nonetheless, the judge ruled that an eviction is warranted based on Veldhuizen’s intention to carry out works, which, given his situation (construction stop!!) can in no way be defined as urgent. The invincibility of real estate criminals in a constitutional state that seems to solely protect big money is once again painfully exemplified.

September 2019 – Amstel 45 squatted

September 2019 – Amstel 45 squatted

Etc…

There are uncountable examples of owners going unpunished when neglecting their properties, whereas the promise (or policy) of no evictions for emptiness has increasingly become a forgotten or naïve concept.

The bakery on Buikslotermeerplein, which was squatted this summer after years of emptiness, is currently managed by a number of bicycles, but otherwise nothing significant seems to be happening. Where once was an enormous DHL warehouse on Hornweg, squatted in May and lived in for about six weeks, is now an empty, fenced in site with a sign and an empty promise to build something big and beautiful (in 2018!). The for the umpteenth time squatted pizzeria on Statenjachtstraat was evicted on the grounds of urgent asbestos removal, but after months of repeated emptiness, all that changed is a fence around the building, holding yet another empty promise of construction nowhere to be seen. The buildings on Jan Hanzenstraat, squatted in spring, were evicted after a few months for plans that were never implemented and virtually nothing is happening with the church on Nieuwendammerdijk that was squatted shortly at the beginning of this year.

The list goes on, but as a final example the former discotheque on Buikslotermeerplein is worth mentioning.

September 2020 – former Pizzeria on Statenjachtstraat, Amsterdam Noord

September 2020 – former Pizzeria on Statenjachtstraat, Amsterdam Noord

The Disco

The building on Buikslotermeerplein had been squatted once before by We Are Here in 2018. At the end of the summer, the building was again put to use as part of a nationwide protest against a legislative proposal for a stricter enforcement of the squatting ban. The disco, which hasn’t been in use for many years, is owned by the municipality, who left the building vacant in all this time. With the arrival of the north-south metro line earlier this year, the value of this property will increase considerably, as will properties in the rest of the neighbourhood and many other areas in Amsterdam Noord. The Buikslotermeerplein is located at the final station of the new metro line and in the upcoming years will become yet another hub of yuppification and gentrification. For the time being, the plans for rebuilding and modernisation of the shopping centre seem to be postponed and the disco still remains empty. We Are Here had to leave because the municipality claimed the building was actively in use by a furniture restorer. After the eviction, any sign of life remained absent (apart from thick layers of fast-growing, colourful mould) and during the resquatting this summer, no visible evidence of use or works could be detected anywhere. The municipality has been caught lying, but again decides to criminally evict on the same grounds. Where once people used to dance (most likely to horrible music), it must now remain silent until here too the sound of bulldozers and demolition machines mute the protest of housing activists.

15 september 2019, National day of action against the squatting ban, Buikslotermeerplein 7 resquatted

15 september 2019, National day of action against the squatting ban, Buikslotermeerplein 7 resquatted

New law (or no law?)

At the beginning of the summer, squatters in the Netherlands were shocked by news of a legislative proposal put forward by Mister Koerhuis (VVD) and Mister van Toorenburg (CDA). Their ‘Law for Enforcement of the Squatting Ban’, was to signal the end of squatters’ ‘unpunished crimes’. By changing legal procedures, a Judge-Commissioner could order an eviction within three days at the request of a public prosecutor, without having to consider the squatters’ perspective. This would completely circumvent the concept of house peace fought for in 2010. Just like back then, squatters from all over the country came together to demonstrate their resistance and on September 15 several protest actions were held in various cities. People also didn’t let themselves be intimidated during the rest of the year and still squatted in different places (with varying degrees of success).

Winter 2019, Asterweg 15C shortly resquatted

Winter 2019, Asterweg 15C shortly resquatted

At the end of the year, the law hasn’t been implemented and the proposal seems to have failed. This proposal was not the first attempt by these gentlemen to enforce stricter procedures for squatters. Earlier they had submitted motions as well as questions to the Second Chamber. In their motivation for this new law, they write about poor, fooled property owners being unable to recover financial damages from criminal squatters, who hop anonymously from building to building, leaving a trail of destruction behind. The image they aim to create is ridiculous in itself, but, smart as they are, the examples mentioned concern precisely those groups that were often received and described positively by media and neighbours. Particularly striking however, is the enormous attention they direct towards We Are Here.

We Are Here

The group of denied asylum seekers, who have actively been squatting buildings for nearly eight years now in order to provide accommodation for people in precarious situations, known as We Are Here, have been attacked regularly from various sides over the last years. Several of the buildings they lived in have been assaulted by extreme-right groups, who were protesting their existence in general. Windows and walls of buildings have been smeared regularly with racist slogans and nasty threats. Demonstrations took place, during which housewives with their brothers and nephews (or however else they know each other), banners and Dutch flag in hand, under safe supervision by the police, were shouting clever slogans like “Ghana Africa back!” or “Illegal is criminal!”, before being escorted to the train or bus back to whatever village they came from for this fun group outing.

The media has played a major role in these increasing expressions of hate due to their predominantly negative reporting and explicit mentioning of the addresses of We Are Here squats. A well-known incident took place in a squatted building in the Westelijk Havengebied in Amsterdam. When the owner stormed the building with a camera team, this group of ‘illegal’ squatters had the courage to protect their house peace and refuse this man access to his premises. The media condemned the group, social media shouted even louder, and naturally certain politicians couldn’t let this incident pass uncommented.

Soon after, mayor Halsema responded in an interview on AT5, promising to critically inspect the squatting policy to figure out how to deal with these abuses and even mentioned employing the immigration police. By the end of the year, she is speaking of a new policy that is supposed to live up to her promise.

In the meantime, the latest ‘conquest’ of We Are Here is an entirely derelict parking garage in Zuid Oost. This place literally doesn’t offer more than a roof; there are no walls, no water or electricity and people sleep in tents. This is the danger the extreme right is warning of and the mayor seems to fear. These are the so-called parasitic criminals, who constantly acquire luxuries to which they have no right?!

While mayor Halsema concludes 2019 with a shameless display of what she stands for and what she wants for the city, another group of people takes the opposite stance in this first week of 2020. During a working day in the We Are Here garage experienced squatters and sympathisers helped building walls and rooms and within a very short amount of time a big part of the building became significantly more liveable and pleasant.

March 2019 – Garage Kempering on Karspeldreef, Bijlmer, the former Vluchtgarage, squatted by We Are Here in December 2013.

March 2019 – Garage Kempering on Karspeldreef, Bijlmer, the former Vluchtgarage, squatted by We Are Here in December 2013.

Halsema’s letter

In a letter to the city council at the end of December, the mayor of Amsterdam reports on policy changes made “to improve the execution of the squatting ban”.

Just like Koerhuis and Van Toorenburg earlier this year, the majority of her letter discusses how the We Are Here group and more specifically the incident in the Westelijk Havengebied has inspired the triangle (mayor, public prosecutor and chief of police) to change the squatting policy.

Echoing her right-wing colleagues, she emphasises the injustice of squatters’ upheld anonymity and clever abuse of the constitutional system, for example by starting court procedures merely to delay an eviction.

To put an end to this deplorable situation, three points of the policy must be adapted:

• “investing in information position”: To obtain a clear image of recidivist squatters, evictions won’t always be announced. As a result, squatters don’t get the chance to disappear prior to an eviction, therewith enabling the police to arrest the squatters and establish their identities.

• “judicial process”: The court will schedule summary proceedings within 2 to 3 weeks, instead of 6 to 8 weeks. Furthermore, the court will, if possible, give the verdict immediately and, in the event of a negative verdict, will promptly determine the date of eviction.

• “intervention in the event of a red-handed act”: Instead of first investigating the actual situation, as was previously the case, the police will directly intervene in events of red handedness to prevent the establishment of house peace. Should the risk for escalation be too high, consultation must first take place within the triangle.

February 2019 – Squatted Augustinus church on Nieuwendammerdijk 227

February 2019 – Squatted Augustinus church on Nieuwendammerdijk 227

What will really change then?

An eviction without official announcement is only permitted in the exceptional case of a speed eviction. Other concrete measurements to identify squatters are not mentioned.

Summary proceedings are regularly scheduled earlier than in 6 to 8 weeks, and if the date of eviction is announced with the verdict, the first policy change seems to be somewhat undermined. The fact that squatting becomes a greater priority on the court’s agenda is outrageous, if you imagine how many matters of actual urgency it must contain.

As for the third point, it has always been an important part of a successful action that squatters have established house peace instead of being caught red-handed by the police when opening a building. There is no mention of a change in definition of red handedness, so nothing much seems to change in this regard.

Halsema concludes with an affirmation of no evictions for emptiness.

All in all, the letter partly seems to be all talk to make a few right-wing friends, satisfy angry property owners and fearmongering media and above all to create an image of herself as a major, who actively tackles problematic issues and is certainly not the left little girl people still have in mind.

The employment of immigration police against We Are Here doesn’t resurface in her letter. In an emergency debate requested by Groen Links council members, who demanded clarification on this issue, Halsema answered ominously that “illegals, who don’t commit crimes, have nothing to fear.”

In other words: illegals who continue to squat do?

So…

We are being confronted with a stricter policy and even though the emerging risks are still unknown, we will have to take them together no matter what, as they will apply to all of us. The increasingly negative attention in the media and politics, which has been noticeable for many years now, can only be fought by posing a collective opposition. Similarly, the growing demotivation and despondency amongst squatters can only be overcome by showing each other that we are still there and to take action together in order to fight for our version of a liveable city. While the number of squatters in the city has shrunk considerably, the number of people that is dealing with or will be dealing with consequences or aspects of this housing struggle, is growing. Given the increasing number of homeless people on the street and the decrease of affordable housing in the city, the urgency for radical autonomous solutions is becoming more relevant by the minute.

Luckily, more people realise this…

Niet te koop

This action group has been fighting the sale of social housing in the city since 2016. Under the name ‘Niet te koop’ a large number of tenants, activists, students and sympathisers have joined forces with tenants’ associations and existing groups such as Recht op Stad, Bond Precaire Woonvormen, and Fair City. Their protests involve for instance the squatting/occupying of buildings in order to remind social housing corporations and politicians of their responsibility to provide affordable living space in an increasingly expensive Amsterdam.

Sloterweg

At the end of October, three cute little houses on Sloterweg 711-713 were squatted. The municipality was going to demolish these former workers’ houses to make way for self-construction plots so as to offer the wealthy space for their expensive villas. For many local residents and other admirers of beauty, these little buildings are of great historical value, since they are the last remaining houses of this kind that were typical of the once so idyllic streetscape in this neighbourhood.

The squatting of these buildings has caused the struggle for their preservation to flare up considerably, even though the group couldn’t live there for very long. An eviction followed within weeks of the squatting, but neighbourhood residents and other sympathisers have continued to protest the plans of the municipality and therefore this heritage disaster could still be averted.

In a somewhat more optimistic bout, there certainly are some positive things to be said about last year. Evictions have always been part of squatting and most people in these circles have never had faith in a just juridical system. Nevertheless, 2019 also brought a triumph that is enormously rare, and therefore also extremely relevant for the squatters’ movement.

October 2019, Sloterweg 711-713 shortly squatted

October 2019, Sloterweg 711-713 shortly squatted

Het Klokhuis (The apple core)

No joke… On the 1st of April 2019, a group of squatters won their lawsuit against the state! The Kinderen van Mokum have been actively squatting buildings in the city for some years now and as a group they draw attention to the well-known disastrous situation on the housing market, which is becoming more and more inaccessible, certainly for the younger generation of Amsterdammers.

On September 30, 2018 they squatted Zeeburgerpad 22, the 6th resquat of one and the same building, which they named ‘Het Klokhuis’.

Since 1990, the owner Appelbeheer BV has repeatedly left the building empty for long periods of time, yet still managed to somehow convince the OM (Public Prosecution Service) to evict. On February 22 an eviction notice arrived in the letter box for the umpteenth time. The residents of the Klokhuis started a court case against the state, argued for a complete prohibition of the intended eviction and the court ruled in their favour!!!

October 2018 – Het Klokhuis, Zeeburgerpad 22 freshly resquatted

October 2018 – Het Klokhuis, Zeeburgerpad 22 freshly resquatted

So, there is still hope… Or something along those lines…

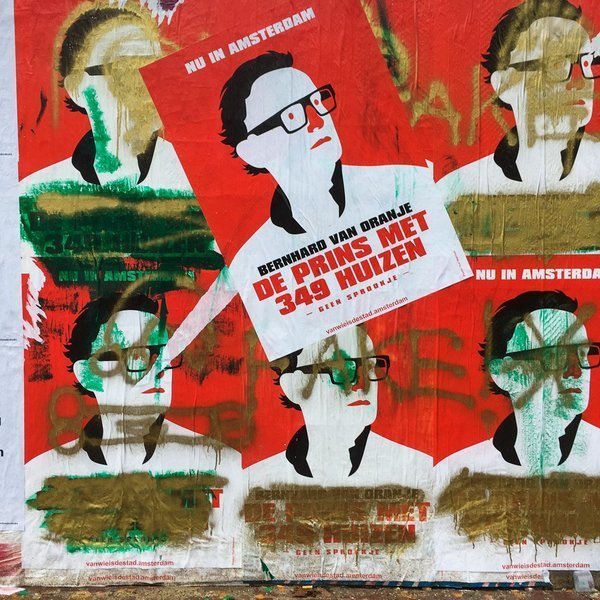

It is obvious that the necessity for squatting is still there, maybe more so than ever. House prices are skyrocketing and the waiting lists for affordable rental properties are so rapidly growing that some will literally never get their turn. Gentrification has by now caused nearly every neighbourhood, where people with low incomes live, to become too expensive for their residents, almost every nice place has been transformed into a plastic hipster hangout and the city offers more facilities for tourists than for Amsterdammers. And so on, blablabla… we all know this by now. Luckily, more people seem to be waking up. Next to the negative attention squatters received in the media, there has also been more reporting on certain individuals, who own hundreds of properties with which they shamelessly speculate, causing the housing market to explode. As the royal example, Prince Bernhard Junior, nephew of the king and ambitious businessman, is frequently mentioned. The Volkskrant published an article on 04.11.2017 containing an overview of the largest players on the Amsterdam real estate market. With only 102 properties, Prince Bernhard is by far not on top of the list of big fish. Next to names like J.C.M. Veldhuijzen with 512 buildings and J. Rappange with 449 properties, our prince seems far from being the king on the housing market. Companies like Liander Infra with 2357 buildings and Bouwinvest Dutch Institutional Residential Fund with no less than 5401 flats compete with foreign investors like the American investor Blackstone that bought Dutch rental properties for 200 million euros only this year. As a result, the prices for an average flat are rising and even though some politicians are calling for measurements to better regulate the market, truly adequate solutions from the political spectrum are, needless to say, lacking.

Satirical poster of Prins Bernhard Junior

Satirical poster of Prins Bernhard Junior

There is talk of an approaching bubble on the housing market while an actual housing crisis has been and still is going on for quite some time now.

There are visibly more homeless people in the city and despite Halsema claiming in her letter that there is significantly less emptiness, still some 600.000m2 of office space remain empty, often displaying vacancy management posters behind the windows indicating unused space. Halsema maintains to retain the policy of no evictions for emptiness but has repeatedly violated this policy without any shame. Anti-squat posters appeared in the windows of the disco, which was squatted to emphasise her hypocrisy, making her lies blatantly visible. Even the ADM is factually still standing empty. She shows to rather do business with criminals than entering a dialogue with squatters or activists. And even though deals like the ADM and the Lutkemeerpolder have been concluded for some time, the explicit criminal nature of these affairs could have been reason enough to dissolve the agreements or at least hold off until further investigation. Yet, agreements made with criminals are seemingly binding for this mayor and her city council, while international human rights conventions and Amsterdam’s long-standing tradition of protecting minorities are non-binding options that can be carelessly swept off the table.

She threatens with the employment of the immigration police against We Are Here, with violating squatters’ legal rights in general and this group’s rights in particular. We will most likely have to deal with fiercer police action and also the hateful smear campaigns in the media will certainly be continued this year.

In 2019, we had to suffer quite some blows and we also expect the strong arm to strike no less mercilessly in 2020. Is it time to fight back?

The social housing struggle that we squatters are involved in by default, will become more tense, but you cannot claim to fight for something, if you are too afraid to receive any blows. I do not necessarily want to call on people to pick up sticks and stones and go out into the streets to literally fight authority, but we will have to arm ourselves against a growing collective threat.

Make sure that you stay on top of the ever-changing rules of the game. Inform yourself, but especially each other of the problems we will have to face and the options that have been come up with to handle them. Sharing practical and legal knowledge and an open attitude towards deviating ideas, alternative strategies and creative plans is essential for a movement that sometimes seems to be fairly stuck. There is no room for elitist clique behaviour so as to feel better than the rest of the world, because we are the ones, who understand what is wrong with it. We must reach out to all individuals and groups that fight for a better city and instead of regarding our differences as exclusive factors, we should view them as potential additional value to a struggle that will have to be fought on many societal levels. Anyone who has like-minded thoughts on justice and a more social world, is a potential ally and of those you can never have enough. Everywhere, there are duped tenants, homeless students, young climate activists, social justice activists, anti-racism radicals, angry inner city residents or “simply people, who think squat parties are much more enjoyable than Paradiso or something” and they all need a space, where they can complain about how things are only getting worse.

So, let’s continue to look for unused spaces not only to live in, but also to offer places, where we can imagine together what a better world might look like and put our ideas into practice immediately.

Or, you know… Let’s squat!

(This text has been sent to the editors of the Jakra 2019. Some of the pictures above published are from Hans.)

(Other important, valuable publication in 2019: Architecture of Appropriation. On Squatting as Spatial Practice)

Some squats in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/groups/country/NL/squated/squat

Groups (social center, collective, squat) in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/groups/country/NL

Events in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/events/country/NL

Source: Joe’s Garage: https://joesgarage.nl/archives/15184