Instead of unconditionally gifting half a million euros of public money to Van de Putte’s property portfolio, Ivicke must be expropriated before it can be restored. Only then is its future secure.

Instead of unconditionally gifting half a million euros of public money to Van de Putte’s property portfolio, Ivicke must be expropriated before it can be restored. Only then is its future secure.

The province of South-Holland pledged to pay 500,000 euros for Huize Ivicke’s restoration if the municipality of Wassenaar is unable to recover the costs from the owner, Ronnie van de Putte.

This amounts to yet another handout of public money to a parasitic financial firm.

The move comes after the municipality of Wassenaar placed an administrative order on van de Putte last November which supposedly compels him to complete Ivicke’s restoration by July, 2020. Van de Putte contested this order in court, but lost.

In the event that van de Putte does not comply with the administrative order, the municipality of Wassenaar said they will arrange for Ivicke’s restoration and send him the bill. A spokesperson for the municipality of Wassenaar described this scenario as “unlikely,” but past experience tells us otherwise. Ask Amsterdam, Sluis, Noordwijk, or Leiden.

Rather, given van de Putte’s history and the current financial and legal difficulties facing his companies, the province of South-Holland’s 500,000 euro pledge means there is now a very real chance that the taxpayer will subsidize the profits of a notoriously unscrupulous millionaire property speculant.

Van de Putte made his fortune by leaving properties empty and destroying them. While he invariably promises city officials that we will carry out much-needed works, his development proposals for the properties he owns never go beyond a pleasing artist’s impression of his vision.

He is a property speculant, not a developer. He profits from what is called the housing crisis but what is simply the financial housing market at work. His business model is to neglect properties of particular public interest, leave them to rot, and wait until local authorities blink and buy him out at an inflated price.

All of this has been known for decades. The shady dealings of van de Putte’s maze of companies date back to the 1980s. Since February, he has sold Ivicke twice to two of his own newly-established companies registered this year in Belgium. First Ivicke was sold to RAP B.V. then it was passed on to Monumenten Restauratie B.V.. If further proof was needed that van de Putte is taking the piss, then the latter name choice for his new company is exactly that.

Time and again he has held properties to ransom, deceived municipal officials, distorted the market and profited at the expense of taxpayers. By committing public money to one of van de Putte’s financial assets with zero conditions, the province of South-Holland and the municipality of Wassenaar have made themselves complicit.

Perhaps it is the case that the 500,000 euro pledge is a bluff to force van de Putte’s hand. After all, the municipality of Wassenaar needed extra weight to back up its tough talk towards him given they cannot fund their own heritage department following VVD-led cuts, nor take care of monumental buildings they have owned since the 1980s which have now fallen into disrepair. We’ve already seen that van de Putte would rather carry out shoddy, cheap emergency repairs himself than let the city do it and send him a bill. So, if the municipality of Wassenaar and the province of South Holland’s concerted action does finally force him into action, we can at least expect that the restoration works will be a smokescreen: done at the lowest possible cost, without respecting the building’s monumental character, simply to get the city authorities off his back. Or it could end up lost to a fire, like some of his other monumental properties.

If, on the other hand, the 500,000 euro pledge is not a bluff and van de Putte stays true to his form of the past, then he looks set to eat up a huge chunk of the province of South Holland’s reserves for the restoration of monumental buildings. According to the 2020 budget, there is 2.5 million euros available for this. There are two other monumental properties set to receive some of this money. Half a million is going to de Tempel, a garden estate owned by the municipality of Rotterdam.

The other is Het Huys ten Donck in Ridderkerk, which will get almost 750,000 euros. This property has been in the possession of the family Groeninx van Zoelen for over three centuries and is currently owned by Stichting Het Huys ten Donck which facilitates various elitist events there.

Of note in South Holland’s budget report for restoring monumental buildings is a provision stating they “want monumental buildings to be (re)-used, so that they fulfil a contemporary function and are accessible to the public as much as possible.”

The province of South Holland’s Cultural Heritage Policy Vision 2017-2020 goes even further. This document states that “high priority is given to the sustainable/resilient use of national monuments. By stimulating restoration as well as repurposing, historic buildings will remain in use and preserved for the future.”

With regards to de Tempel, this can be all but guaranteed. With Het Huys ten Donck, it is mainly accessible to rich customers, but at the very least it has a function. With Ivicke? There is not even the beginnings of a plan for its subsequent use after restoration. How can the province of South Holland justify blowing 20 percent of their reserves unconditionally on a project that clearly does not meet their own criteria or vision? Further, in the absence of any plan for Ivicke, we, the squatters who intervened against the estate’s destruction, face two separate eviction proceedings from both van de Putte and the municipality of Wassenaar.

The province of South-Holland’s move is not a workable solution to tackle a systemic problem. There must also be meaningful coercive measures that reduces the likelihood of lost public money. Hundreds of monumental buildings are at risk throughout the Netherlands. Are provincial authorities going to bail out every neglectful owner of a monumental building and allow them to enjoy the rewards? What of those owners of monumental buildings who work hard and spend big to keep their property alive?

The only way to tackle speculants like van de Putte who have played the financial housing market like a game for decades is to take away their toys. Ivicke and all other properties kept empty and neglected for financial speculation must first be expropriated for public use before funding their restoration with public money. This is how properties like Ivicke can be restored properly and then cared for by those who use them, whilst combating the violence of the financial housing market.

The only way to tackle speculants like van de Putte who have played the financial housing market like a game for decades is to take away their toys. Ivicke and all other properties kept empty and neglected for financial speculation must first be expropriated for public use before funding their restoration with public money. This is how properties like Ivicke can be restored properly and then cared for by those who use them, whilst combating the violence of the financial housing market.

Huize Ivicke

Since squatting Ivicke, we’ve made the building wind and water-proof, installed electricity, plumbing, and heating, and maintained the grounds.

We squat to live and to protest against the financialization of the housing market. When housing is seen as a financial commodity rather than a basic need, opportunists (property speculants) like Ivicke’s owner Ronnie van de Putte are incentivized to neglect and keep perfectly habitable buildings empty in the hope of its demolition and a new, more profitable, development. Or, perhaps in Ivicke’s case, to hold the property hostage and extract an inflated price from the municipality, directly at the public’s expense.

The consequence of this financial system for housing is there for all to see. Rapidly-rising property prices encourage housing corporations to force the original inhabitants of city neighbourhoods to leave, small-scale farmers are pushed off their land, and insecure forms of tenancy such as anti-squat and temporary rental agreements become the new normal.

Politicians and the media refer to such problems as the “housing crisis,” which is characterized as a problem of supply and demand. Squatting demonstrates that it is not a problem of supply. There is more than enough vacant property and derelict land to meet people’s needs. The problem is one of use and access. Because for financiers, property speculants, and the politicians they bankroll, limiting use and access, violently if necessary, is required for a “healthy housing market.” Huize Ivicke, with its monumental status and give-no-fucks owner, is simply an extreme example of what passes as perfectly normal in the financial housing market.

Our presence at Ivicke and the work we do, by any reasonable, well-informed opinion, is a benefit to the building. It remains unclear what story van de Putte will spin next about his plans for Ivicke. His lawyers have started court proceedings against us, but have not outlined any intentions for Ivicke’s use.

Meanwhile, the municipality is also preparing eviction proceedings against us. Until a few months ago, they largely tolerated us because we are cooperative in the interests of the building. But without a concrete plan and use for Ivicke, they risk doing van de Putte’s work for him and creating another situation of vacancy and neglect.

For now, we continue to do what we’ve been doing since July, 2018. Living in and caring for our home.

Who is Ronnie van de Putte?

Name: Ronnie van de Putte

Nicknames: Krottenkoning, Van de Beerputte

Business model: Financial speculation and extortion of public money

Portfolio:

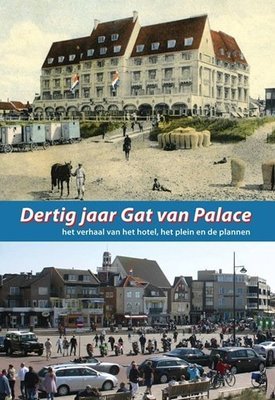

Nordwijk: Gat van Palace (Palace Hole), burnt-down riding school, burnt-down printing house, various always-definitely-soon-to-be-developed-this-time-for-sure plots and properties

Leiden: Het Gat van Van de Putte (Hole of van de Putte)

Sluis: verpauperd niet-meer-te-redden klooster (run-down, no-longer-to-be-saved monastery)

Amsterdam: hundreds of neglected apartments, inflation of a housing bubble in cooperation with banks

Wassenaar: haunted house Ivicke

Preface:

Ronnie van de Putte, the owner of the squatted Huize Ivicke, is usually described by the media as a project developer, property magnate or the Krottenkoning (slum king). Few publications mention that it was squatters who gave him the latter name in the 80s. It is the most accurate one as RvdP is known nationwide, as well as in Belgium, for the ruinous neglect, dilapidation and abandonment of his stately properties.

He is a speculant, or as the Dutch say, a ‘huisjesmelker’, a manipulator and a real estate gangster. Over the top? Well, what else would you call somebody who profiteers from the housing system, neglects their legal duties, deceives authorities and business partners, doesn’t pay their debts and sends thugs to intimidate tenants?

Here’s a tale as old as time, of a rich and seemingly all-powerful supervillain Ronnie van de Putte, his useful idiots (starring various mid-level bureaucrats), and the ones who put up a fight – those pesky squatters out to destroy all that is Good and Holy by disregarding property laws and offending bourgeois sensibilities. All against the backdrop of a corrupt and inhumane land, in which greedy speculants are given free reign to extract every last penny out of the law abiding, peaceful and tolerant (to all sorts of abuse) population – Gotham. I mean, the Netherlands!

CHAPTER I: The Rise of the Villain

Ronnie van de Putte’s story begins in Amsterdam in the mid-70s, when the city welcomes the likes of him to buy and split rental properties with wild abandon. Banks enable this by financing RvdP and other speculants with cheap loans. By the beginning of the 80s, Ronnie ‘Van de Beerputte’ accumulates a thousand properties, and gives city authorities the first glimpse of his modus operandi by neglecting maintenance on many of his apartments. But he needn’t worry, as the municipality kindly takes over his responsibilities to his tenants. RvdP is allegedly busy collecting key money and sending thugs (knokploeg) to deal with squatters.

The bank loans and speculation create a housing bubble*. The bubble goes *pop*. RvdP has so many houses and so much debt he’s about to go bust, and even the happily lending banks are scared he’ll take them down with him. The banks agree to the municipality buying 559 homes, 33 commercial properties and 15 squatted properties for 12.5 million guilders. And this is just the first of the public bailouts RvdP and his buddies will receive in his long real estate career.

Like every good villain, RvdP emerges from this crisis scratched but as the saying goes, what doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger – like falling into a pit of nuclear waste and gaining superpowers, or filing for bankruptcy and getting rewarded with a bailout.

In the meantime, Ronnie starts working his charm in Noordwijk. He buys a seafront hotel in 1978 and promises to restore it to its former glory to create a restaurant, a bar, a bowling alley, or maybe a hotel, or apartments… and does nothing. Fire breaks out in the building in 1980. The hotel falls into total disrepair and is demolished. All that is left from it 40 years later is the ‘Palace Hole’, and it’s just the first of RvdP’s properties that is so notable as to get a nickname.

RvdP owns more properties in Noordwijk. A plot near the hotel, which he also promises to develop. The Vuurtorenplein, a square with properties that remain mostly empty or squatted. A former riding school, which burnt down multiple times. A printing house that also burnt down. Ronnie must be in the Guinness Book of Records for most properties lost to fire, such bad luck.

Is it so hard for him to find tenants that would protect his buildings from burning down? No, he doesn’t want them. According to the minutes of the 2018 general shareholders meeting of Bever Holding (a stock exchange-listed company that RvdP bought in 2007 that now owns all of his properties), they ‘prefer not to have long term tenants’. End scene.

Meanwhile in Leiden, RvdP leaves another gaping hole. This one will be called ‘The Hole of Van de Putte’. In 1993, Ronnie buys a building opposite the central station. It’s demolished in 2001. It seems that this time he has a solid plan for the lot and the neighbouring squatted building. But the hole wouldn’t be a hole, and Ronnie wouldn’t be the Krottenkoning, if he didn’t purposefully neglect it. According to Bever, it was the municipality’s fault for having spatial regulations in place or something. According to others, it was a deliberate strategy to again extort public money. Guess which one it is? In 2010, the frustrated city of Leiden buys the Hole for an inflated price of 18 million euros, and Bever and van de Putte make a profit paid for by the taxpayers.

Another municipality, Sluis, also has a problem with the Krottenkoning. Here he buys a former monastery and boarding school Het Hoompje in 1992. The beautiful building is never put to use, and continues to fall apart. In 2019, the municipality deems the building to be beyond repair but later decides to continue to pressure Ronnie to fix it.

CHAPTER II: A Game of Cat and Mouse

How can somebody like Ronnie to do what he does for decades? How can public officials allow, or worse, enable this to happen?

The municipality of Noordwijk has tried to force RvdP to maintain and develop his properties by imposing fines and penalty payments. These would usually get waived once Ronnie came up with a new plan. After fines were withdrawn, the plans would again stall. In 2017, RvdP’s fine had risen to over half a million euros and after a number of court cases, he finally paid three quarters of the penalty. Development company Volker-Wessels offered to help develop the holes with Bever but this also never happened. The former mayor of Noordwijk, Jan Rijpstra, said:

‘That is surely my biggest deception. A frustration file of which there is no other in the Netherlands.’

Yet he’s not the first and not the last one to get deceived by Ronnie’s shenanigans.

Peter Ploegaert, the Sluis councillor dealing with Ronnie over Het Hoompje, said that in his municipality Volker-Wessels also gave confidence that the development of the former monastery will begin. He said:

‘I finally got things moving, I thought. That was naive of mine, vain hope. (…) I heard nothing from Bever and agreements were not kept. The periodic penalty payment has expired, we are back to square one.’

The municipality never managed to retrieve the 150,000 euro in fines.

RvdP was investigated for fraudulent conduct, together with the banks that financed his properties in Amsterdam, but it came to nothing. Indeed, Ronnie van de Putte has never been convicted of financial wrongdoing, but – crucially – not in the same way that you or I have never been convicted of financial wrongdoing.

The municipality of Leiden tried to expropriate his property but lost in court. Others try to use administrative orders but RvdP always challenges their legality.

There are no rights like property rights in the Netherlands.

CHAPTER III: People vs Krottenkoning

Ronnie van de Putte couldn’t have a worse reputation. He’s proven time and time again that he’s not to be trusted and that he’ll go to great lengths to deceive councillors. The current mayor of Wassenaar, Leendert de Lange, knows this all too well from dealing with him whilst he was an alderman in Noordwijk. Yet RvdP is given another chance, this time to repair Huize Ivicke. It’s clear to almost anyone that he does not want to do it. But Wassenaar city council are willing to continue this game of cat and mouse without changing their approach, and yet expect different results.

The province of Zuid-Holland announced recently that it will subsidise the restoration of Huize Ivicke, if RvdP does not do it, and the municipality of Wassenaar cannot recover the costs of doing it themselves. That is, it will spend 500,000 euros to repair the private property of Ronnie van de Putte, who will be able to keep it and profiteer from it in the future. This would be yet another outrageous transfer of public funds into the hands of a notorious speculant.

What’s really worrying is that the conversations between municipalities and RvdP take place behind closed doors, which protects them all from public scrutiny. It also raises questions about corruption that could be happening to appease bureaucrats who, for some reason, keep entertaining Ronnie’s implausible plans. These councillors and mayors, rather than resolving the problem, are part of it. They are Ronnie’s useful idiots, well-meaning or not, complicit in this whole situation.

Earlier this year, RvdP demolished the riding school and the printing house in Noordwijk. Alderman Henri de Jong said recently there have been ‘constructive conversations’ in a ‘positive atmosphere’. This approach only validates RvdP as a legitimate property owner and business partner.

Politicians and the media go along with this circus and portray the situation as some sort of aberration, and Ronnie van de Putte as an elusive villain – a bad apple in the world of real estate. But he’s not Krottenkoning, a comic book villain. He is not an exception to the rule. He and others like him are products of a financialized property system that treats homes as commodities. What are much needed resources are instead traded and speculated upon for profit. Politicians and city bureaucrats are not here to put a stop to this – they enable and guard the transfer of public funds to crooks like Ronnie van de Putte.

It should be unthinkable that Wassenaar officials would continue to enable Ronnie van de Putte’s business model. What they’re doing is humouring a criminal and pretending that his intentions are serious. If they are genuine about the future of Ivicke, they are going to be humiliated. If, however, they know that Ronnie is never going to meaningfully restore and maintain Ivicke, and are only keeping busy to score political points – well, that also wouldn’t be surprising.

As things stand, the state is willing to fund Ivicke’s restoration with zero conditions. On the other hand, we, the residents of Ivicke, have been threatened with a fine of 100,000 euros. We are certain we won’t have the option of ignoring this, only to have it written off by the state.

The only way out of this sticky mess would be to take out the one who is shitting on the negotiating table, and expropriate Ivicke from Ronnie van de Putte. Only then can it be restored properly (safe from another unfortunate fire…) and secured in the long-run. Whatever the city authorities say about “saving Ivicke”, while it remains in RvdP’s hands it will always be under threat. Ivicke must be expropiated from him if it is to have a future. And this must serve as a precedent against all parasitic real estate speculators who insist on hoarding properties and extracting profit at everyone else’s expense.

In the meantime, Ivicke is in good hands with us. With zero external support outside the squatting community, we maintain, make repairs and prevent the building from sliding into further decay: something no municipality facing down RvdP has been either able or willing to do.

Further reading: De Nieuwe Elite Van Nederland

* A housing bubble is when properties are grossly overpriced by investors buying up limited resources (those who need houses are in competition with them). The investors are given an upper hand in the race by cheap lending and favourable housing market regulations, for as we know, regulations are there to be loosened and our investors need to be rewarded for pumping all this magic air money into the economy! At some point somebody has the ‘hang on a minute…’ moment. Bankers, politicians, property owners etc. start realising that this whole clusterfuck is unsustainable, the bubble goes *pop*, people lose houses. Have lessons been learnt? No, the clusterfuck continues and generates new bubbles. You live in one now.

Huize Ivicke

Rust en Vreugdlaan 2

2243AS Wassenaar, The Netherlands

ivickeautonoom [at] riseup [dot] net

https://squ.at/r/64fv

https://huizeivicke.noblogs.org/

Some squats in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/groups/country/NL/squated/squat

Groups (social center, collective, squat) in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/groups/country/NL

Events in the Netherlands: https://radar.squat.net/en/events/country/NL

Source: Huize Ivicke Autonoom

https://huizeivicke.noblogs.org/post/2020/05/13/huize-ivicke-restoration-through-expropriation/

https://huizeivicke.noblogs.org/about/

https://huizeivicke.noblogs.org/the-owner/