Can Vies social centre in Barcelona recently hit the headlines across the world when its eviction led to five consecutive nights of protest and rioting. But the story is much bigger than that. At the time of writing, the social centre is being peacefully re-constructed and a Can Vies crowd-funding campaign has gathered more than €17.000 already. The goal is to gather €70.000 in solidarity with those arrested during the protests and to buy all the materials necessary to re-build the Social Centre.

Though it might initially seem unrelated, a recent blip in Spain’s history may have played out nicely for the centre’s neighbours: on Monday June 2nd, Spain’s King Juan Carlos announced that he would renounce the throne in favour of his son. The very same day, more than 40 protests were called throughout the country, announcing a period of political unrest. Probably needing to appease the Catalan population, the council offered the squatters a two year lease on the building, an offer they refused. The building has already returned to the control of the local people and they feel no need to negotiate with the authorities.

The context: Squatting in the city of Barcelona

The city of Barcelona has many squats and is no stranger to evictions. For example, La Carboneria social centre was evicted in February this year. Most of the city’s emblematic social centres are now in danger of being evicted, in a clear move to shut down an important hotspot of struggle against the austerity measures imposed by the Spanish government.

Social unrest is further being criminalised through several changes in the penal code. In fact, in July a law could be passed which would severely restrict civil liberties. NGOs, associations and social movements have joined in opposition to these draconian measures. The bill includes four new offences that could carry fines of up to €600,000.

Still, since the start of the crisis in 2008, the vast majority of weekly protests around Spain have been peaceful. The struggle over Can Vies reveals the growing feeling that everyone has a right to the city and reaffirms popular discontent with the government’s perceived authoritarianism.

Also, it seems to indicate that the anti-austerity movement against evictions has contributed to destigmatize squatting. The Movement of Mortgage Victims (Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca, PAH) has managed to halt more than 1000 evictions since its creation in 2009, and helps mortgage-holders negotiate with banks in order to get debt relief. This massive pro-housing rights movement has significantly increased its visibility in the media: through a wide array of squatting actions to allow families to return to their houses and the creation of a couple of PAH Social Centres, the Movement may have contributed to destigmatizing squatting against banks and speculators, when organized by more politicized collectives.

In Spain, mortgage owners who lose their houses are forced to sell them at current market prices. Most of them bought their houses before the sub-prime crash, when prices were going through the roof. By selling their house at current market prices, they lose a considerable amount of money in that transaction, ending up with debt they are unable to repay. Last year, the government voted down the PAH’s Popular Legislation Initiative to change this exceptional legal arrangement; despite the more than 1.500.000 signatures the platform had gathered for the initiative.

Still, it is not the first time that the squatting movement manages to channel popular discontent in Barcelona. Although the first squatting initiatives can be traced back to the late 70s and 80s, a proper social movement with a shared identity only appears around the mid 90s. It is when the government announces a change in the penal code to criminalize squatting that squatted social centres band together and organize as a movement. The year the law was passed, in 1996, a long abandoned cinema (Cinema Princesa) in the middle of the financial district is squatted. The day of the eviction, severe riots take place. The police is at times outrun by the protesters, who manage to force back inside their headquarters, located on the same street: Via Laetana. These symbolic events spark a cycle of struggles in which evictions and repression intensifies, but the number of squats continues to grow steadily.

As the anti-globalization movement emerged in Catalonia, around 2000, the squatting movement lost some of the limelight. Other social movements such as feminism, ecologism, sexual identity movements, and anti-racism become more important, using squatting to promote their own struggles. The squatting movement is deeply rooted but, as this millennium’s economic crisis unfolds, the number of squats seem to diminish in absolute terms.

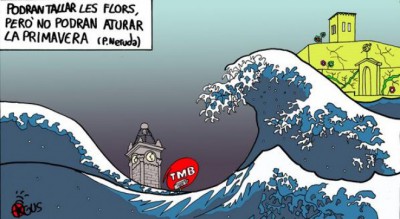

Although social unrest predictably grew under the crisis, nobody could have predicted that Can Vies’ eviction would unleash such strong protests. In a way, this case could be compared to the Taksim Gezi park in Turkey, or the self-immolation in Tunisia that started the Arab Spring, or the small change in the price of bus tickets in Brasil, etc. It is the case of a relatively insignificant event (in terms of the global geopolitical situation) suddenly channelling the rage of the people. As we will see, the Can Vies case differs from others, because 17 years of accumulated squatting experience allowed for a much more articulated and constructive response.

Finally, and although the current changes in the penal code go beyond squatting, history somehow repeats itself with the episode of Can Vies. As explained above, when the penal code was changed in 1996, squatting projects got organized and a proper unified social movement emerged. Social discontent sparked by the transformation of the city because of the Olympic Games of 92 was effectively channeled in the streets by the squatting movement. This time around, squatters have several decades of experience and a wide network of support from several social movements. Is this the beginning of a new cycle of struggles for the squatting movement? As the Can Vies episode clearly shows, accumulated experience has allowed for a much more articulated and constructive response than in 1996, almost 20 years ago today.

The untold media story of Can Vies

What the Guardian described as a “unofficial grassroots civic centre” is, in its own words, a Centro Social Autogestionat: a self-organised social centre, of the sort common to many Spanish and Italian cities. The building had been left empty by its owners, Barcelona’s transport authority, and was squatted in 1997. Since then it had became a well-used and well-loved community space, providing a range of services to the local people of Sants, a neighbourhood with a strong tradition of co-operativism. The centre hosts neighbourhood assemblies, political meetings, workshops, films and concerts. A local newspaper, La Burxa, is produced there.

The City Council planned to demolish the building in order to leave a vacant lot. Negotiations had been dragging on for years, until they finally broke down. In the last few months Can Vies had organised a huge number of activities to demonstrate peacefully against eviction, including benefit concerts, debates and poster campaigns. It is worth noting that a previous attempt at institutionalising a social centre had not gone well: when Casa del Mig left its building to allow the city to renovate it, itwas only permitted to move back into a small office. As the Revista Argelaga collective recently observed:

“It is clear that in the affair of Can Vies, the municipal authorities never had any intention of offering alternatives that were not circumscribed within the bounds of the official bureaucracy, and that at every meeting all they did was engage in manipulation and lying, because by proposing an unacceptable space under government control what they really sought to do was to abolish the free space that Can Vies originally constituted.”

The existence of a self-organised space appeared to be a threat to the city administration and its mayor, Xavier Trias, eventually ordered the eviction. Despite huge opposition (the squat has the support of more than 200 community associations), the eviction went ahead on Monday, May 26. This immediately triggered protests, in Barcelona and indeed in other cities beyond Catalonia, such as Valencia and Madrid. On May 28 there were demonstrations in no fewer than 46 districts of Barcelona.

Inevitably, much mainstream media attention focused on the rioting, which the Telegraph laughably described as being organised by “a small group of troublemakers.” In contrast, Antonio Maestre argues that the supporters of Can Vies were merely acting in self-defence of a centre which had peacefully existed for 17 years. He speaks of the “structural violence of the City Government of Barcelona, which, with a despotic and authoritarian attitude, entirely ignored the interests of the residents of the neighbourhood.” Further, he argues that “Xavier Trías, the mayor of Barcelona, scorned or ignored the citizens whom he is supposed to serve and instead acted in an arrogant, intransigent and irresponsible manner that provoked a violent reaction because he denied the local residents any other channel of expression or negotiation.”

When the Council called an end to the demolition plans on May 29, its hand had already been forced by the destruction of demolition equipment, widespread protests and an announcement by Can Vies that the centre’s reconstruction would begin on May 31. That day, Saturday, several work groups started to clear the space and to recover as many bricks as possible. Hundreds of people formed a line 500 metres long to pass bricks to the site and to deposit rubble outside the district hall. The reconstruction of the centre is now underway. Films on YouTube show the inspiring scenes. And this is the real story – the unreported conclusion to the unnecessary eviction.