[Days two and three below]

On Monday, May 26, police from the Mossos d’Escuadra evicted the 17-year-old squatted social center Can Vies, starting at the atypically late hour of noon, perhaps due to heavy morning rains. Can Vies had an open eviction date, but the choice of day was to be expected as Sunday was elections for the European Parliament (which, incidentally, saw a sharp increase in the presence of far right and far left parties). The party in power never wants to start unpredictable conflicts in the weeks before an election, and the day after an election, the media is full of related news.

People were locked down inside the squat and over a thousand came to show their support, but the police presence was formidable and supporters were kept a couple blocks away; they did, however, block three major roads at the important intersection of Plaça de Sants with banners and chains. All in all, the eviction took about six hours to execute, and the forces of order immediately proceeded to tear the building down.

Can Vies was an emblematic social center in the neighborhood of Sants, and had waged a long campaign of resistance against its eviction, based on legal battles and winning neighborhood support, also allying with transport workers in the CGT (as the building, owned by the rail company, had once been ceded to the union, a fact that enabled Can Vies to win a trial several years back). Can Vies was an important social center in both anarchist and Catalan independence circles (although only the more libertarian wing thereof). In the last months the Barcelona government opened negotiations with them and offered to call of the eviction if they agreed to limit certain activities (e.g. concerts) and pay a symbolic rent. Fortunately the social center refused legalization.

During the anti-eviction gathering, about a hundred people broke away and snaked through the narrow streets of Sants, blocking intersections with dumpsters and taunting police units guarding the back entrance to the squat. People were not masked, but this was only a prelude.

That evening at 8, there was a call-out for a protest to meet in a plaza nearby. A heavy rain began just before the hour, but despite the Mediterranean intolerance for precipitation, over a thousand people came out. Half an hour in, just as the demo was getting ready to start, the sun appeared. And with it, the police helicopter.

A hundred people or more had already masked up, and well, with the aid of umbrellas and a sheltered area in the plaza. Slowly, twenty meters at a time, the demo marched forward, the tension building as it covered the two blocks to Plaça de Sants, within sight of Can Vies. The only police in sight were Guardia Urbana blocking the nearby roads—Carrer de Sants and Joan Güell—a large force of riot cops far behind the march protecting the train station, and one riot van (presumably the first of many) visible on the corner next to Can Vies.

At this point with a megaphone the organizers of the march thanked everyone for coming and announced that the protest was now over (disconvoked, and therefore no longer their legal responsibility), but they added ominously that Can Vies would live on. There was a period of tense waiting, punctuated by the banging of a solidarity hammer on a sidewalk billboard made of some indestructible plastic. Then fifty masked anarchists broke away, charging the cop blocking traffic on Joan Güell. The urbano jumped in his car and sped off, bottles flying in his wake. Wasting no time, the anarchists closed on the satellite van of a progressive TV station and smashed its windows out. A nearby bank met the same fate. Dumpsters were dragged and tipped to barricade the street, and along with the media van they were soon engulfed in flames. Everything was done quickly, calmly, and with determination, and the block stayed, if not tight then at least together, given the variety of objectives being accomplished at the same time. They returned to the march, met with cheers.

Now the anarchists led the march up Carrer de Sants, away from the center. Banks and cellphone stores had their windows smashed out, dumpsters were dragged into the streets, nearly always with someone leading the way to assure that fellow protestors were not run over, and nothing else was touched.

After no more than two minutes, sirens could be heard and flashing blue pierced the evening sky, reflecting eerily off the walls. People began to run but the anarchists held up their hands, many now holding hammers, poles, bottles, or molotov cocktails, and prevented a route. Dumpsters were arranged into barricades and set on fire, and people moved to defend them.

More than half of the protest had already been cut off by the van-charge, more a psychological maneuver than anything else, but there were at least two hundred people, mostly masked, arrayed behind the barricades. A minute later the police charged in earnest, driving over the banner with which some brave and unmasked protestors tried to hold them back, and right up to the line of barricades. Riot squads leaped out, clubs in hands, and the retreat began. Some anarchists tried to encourage a direct resistance, and many objects were thrown, slowing the police advance, but on the wide street the crowd inexorably backed away, eventually breaking into a run as the cops pushed aside the barricades and began another van-charge.

Half of the anarchists went to the right, into a residential neighborhood of narrow streets, and half went to the left, in the direction of the railroad tracks, a zone filled with construction sites and underpasses impassable to vehicles.

Once in these neighborhoods, they quickly stopped running and began defending the streets, blocking the way with burning dumpsters and in a couple cases parked motorcycles. Others began picking away stones to throw. Although the activity was often frenetic, the atmosphere was inspiring. Rioters looked out for one another, communicated on police positions and the best place to set up barricades, when to set them on fire and when not to. Anarchists constantly worked to prevent panic and limit retreats to what was strictly necessary. When running they looked over their shoulders to gauge what police were doing and communicate this to their comrades. People who threw stones in ways that could hurt others were reprimanded; in a characteristic incident someone stomped out a dumpster fire someone else was setting, then apologized and suggested the fire be set once the barricade was in place and not in the middle of the crowd. Many neighbors cheered from balconies or insulted the police. A couple motorcycles were tipped over as barricades and a car with the misfortune of getting trapped by riot police had its windows smashed in the crossfire, but the attitude and atmosphere were consistently more solidaristic, respectful, and calm than on May Day.

Next began a long period of street fighting with the riot police. Barricades were defended, sometimes abandoned, sometimes retaken. Some charges were stopped, others led to temporary routes. After more than a couple minutes of inactivity the crowd preferred to move on rather than risk the police being able to surround them. A couple times divided groups reconverged, sometimes on Carrer de Sants itself, right under the noses of the columns of riot cops.

After a strong campaign against the use of rubber bullets (the kind of high-caliber round of hard rubber that has caused the loss of many eyes, spleens, lungs, and other organs on the streets of Barcelona, and that can also cause death), this crowd control weapon has recently been illegalized. During the riot, the police made heavy use of a couple of their new weapons, but not the water cannon, which would be inoperable in the narrow streets being contested. Their new less-lethal ammo, referred to euphemistically as a “precision-shooter,” is also a type of rubber bullet, a long round ending in a compressible rubber ball the size of a ping pong, that causes extreme pain on impact and makes extremities “fall asleep,” fired from a gun similar in size and shape to an MP5. They also brought out their LRAD sound cannon.

In contrast to Spain’s violent, rambunctious, and dangerous Guardia Civil, the Mossos d’Escuadra of Catalunya are one of the most disciplined, best trained riot squads in Europe (in a different league from the settler states in North America, where cops are less trained in crowd control and in uncontrollable situations escalate directly to military suppression via the National Guard, RCMP, etc.). On May 26, that training was evident. All police charges were disciplined, upon encountering fierce resistance units would stop their charges in unison, small groups of cops never became isolated, aided by the helicopter overhead they were not taken unawares by attacks from other directions in the maze-like streets, and on the occasions when they were forced to retreat by heavy attacks, they would go to the nearest intersection, take shelter behind riot vans and corners, and fire from cover with continuous barrages from their precision-shooters and LRADs. Even in these conditions, masked anarchists sometimes made charges, pushing dumpsters ahead of them as makeshift shields, but the material inequalities were obvious and made themselves felt.

Finally the Mossos made a sustained charge, street by street, on foot with clubs, shooters, and LRAD, backed by their riot vans. On any streets wide enough, the vans were used effectively to break lines of resistance and cause retreats. Once the crowd’s supply of rocks and flammables was diminished and an increasing number of people were screaming, limping or being carried after being hit by the new rubber bullets, the retreat became a route, and the riot cops never gave people the time to resupply. At one point a part of the Black Bloc, by now fractured into at least four groups, retreated onto one of the large streets that crisscrosses Sants, reducing all of the denser neighborhoods to relatively small pockets. They took the opportunity to smash some more banks, but soon the Mossos found them and sent a column of riot vans tearing down the avenue and sending the anarchists running. Once in a zone of large streets, the bloc was dispersed.

Generally, the Mossos used empty riot vans to achieve this dispersal and inflate the appearance of their numbers. In the moment, it is always impossible to know if the van bearing down on protestors is empty, or if there are a dozen cops inside ready to spring out, and when they come four or ten at a time, it’s not a bet that any but the largest or most prepared of blocs is willing to take.

The mossos had a huge number of agents on foot and with the vans, dealing with the various blocs and also pushing back the bulk of the thousand-strong protest, back in the direction of Plaça Espanya, keeping it from rejoining with the masked rioters. In the course of this operation they attacked the offices of the movement newspaper, La Directa, smashing out its windows.

In the end only two people were arrested, although more arrests can be expected. Rioting was substantial, raising the city’s costs for evicting a beloved social center, but far greater than the material damages was the fierce resistance shown to police and the tactical lessons learned.

For Tuesday, May 27, there was a call-out for an evening noise demo outside a government office in Sants, and a more spontaneous gathering when heavy machinery started knocking the Can Vies building to the ground.

From there, things got totally out of control. What follows can only be a partial summary. The most important characteristics are that a day of rage has persisted, surviving the psychological barrier between one day and the next, an extension in time that none of the comrades who were not alive during the dictatorship can remember ever happening in Barcelona; and that things are being organized spontaneously neighborhood to neighborhood.

Around nine in the evening the protest in Sants charged Can Vies and set fire to one of the bulldozers involved in the demolition. It is being said that the machine was afire for four hours. Comrades in Sants barricaded Carrer de Sants, one of the major streets in the neighborhood, for hours, and there were fires and clashes with police.

Comrades close to the center blockaded Av. Paral·lel, one of the major arteries of the city. Comrades uptown attacked the central offices of CiU, currently the ruling party in Catalunya and Barcelona, also barricading major streets around the intersection of Diagonal and Pg. de Gràcia. In the neighborhoods of Gràcia and Sant Andreu, groups of masked people roamed the streets and set up barricades. The newspapers cite disturbances occurring at midnight and later in those two neighborhoods as well as Clot, Poblenou, Nou Barris, and Paral·lel. Banks were attacked, dumpsters and other objects were burned. Accurate figures are hard to come by but there were perhaps a dozen arrests and a dozen identifications the second day.

Police claim a total of 53 dumpsters burned the second day, the figure is probably incomplete. All the riot police from all over Catalunya have been brought to Barcelona. All night long police helicopters were flying over the city with spotlights trying to encounter the troublemakers. Sirens could be heard as police and firefighters raced from one end of the city to the other until at least 3 in the morning.

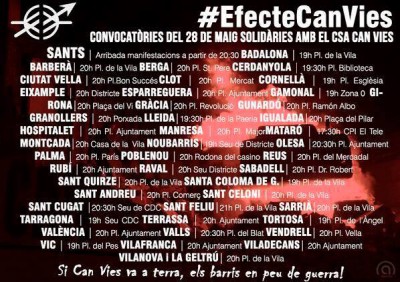

Today there are call-outs for evening protests in Sants and at least 9 other points in Barcelona, as well as 21 towns and cities in the province of Barcelona, six other cities and towns across Catalunya (where, in theory, there will be no riot police), and València, Gamonal (Burgos), and Palma de Mallorca.

It remains to be seen if clashes will continue for a third day and if previously uninvolved people will join in, although a tension grips the city and many people, including those who voted for the conservative party in power, are expressing anger over the helicopters, the state of siege, and the eviction of the social center.

If the revolt extends, it can be assumed that comrades will be happy to learn of solidarity protests and actions in other countries.

If the chronicles of the recent events in Barcelona have turned into summaries and the summaries grow shorter, this does not reflect a diminishing of activity, but the contrary.

During the day, conversations among friends repeated what was more or less insurrectionary common sense: today is the key day. A riot continuing from one day to the next was unprecedented in Barcelona since the end of the dictatorship. Now, if it could continue for a third day, it would have the chance to expand. Otherwise, calm would be restored until the major protest convened for Saturday, politics as usual with or without riots.

Until nightfall, normality reigned, although people across the city were discussing the events. In the evening, people gathered in many different neighborhoods. In Nou Barris, a potentially rebellious proletarian zone, a strong police presence prevented the gathering. In Sant Andreu, a gathering blocked a major avenue with burning dumpsters. Most other neighborhoods went to Sants, probably making things easier for the police to contain, but giving many first-time or unexperienced participants who did not yet feel prepared to take over their neighborhoods a chance to win street experience.

Perhaps 5000 people marched, despite the rain, from Pl. de Sants towards Pl. Espanya, refusing to disperse in the face of a huge police mobilization. Riots started, and for the second time in their history the Mossos d’Escuadra used tear gas. They quickly retook Carrer de Sants, but had to fight corner by corner to go into the surrounding neighborhoods. Riots were dispersed, people standing to fight in groups of 50-500. Fewer hammers, picks, and molotovs were in evidence the third night, so projectiles were in short supply except when rioters crossed with glass recycling bins or construction sites. At one construction site at Pl. de la Farga, site of an old anarchist squat evicted years before, people resisted for perhaps half an hour, eventually forcing the police to retreat and attack from another street. Neighbors gave heavy duty firework rockets to the masked protestors, to use against police. Rioting continued from 9:30 until after midnight.

Many neighbors cheered and banged on pots and pans, others complained and even threw things at protestors (usually only in cases when fires were set on small streets).

In most other towns, solidarity actions stayed within the realm of relatively peaceful protests, although masked protestors in a couple towns in Catalunya damaged or destroyed the offices of the ruling political party with burning dumpsters or other means.

There is another call-out for tonight, and Friday evening, in addition to the big protest on Saturday. People are tired and in many cases injured, but the riot cops have also been pushed to their limits. It remains to be seen if the revolt extends to previously uninvolved people and becomes an insurrection.

There have been around 40 arrests, and many more are expected on the basis of police analysis of photos. Many comrades have also been identified and submitted to biometric photography. On the other hand, the practice of stopping people who film or photograph the riots has become more widespread.